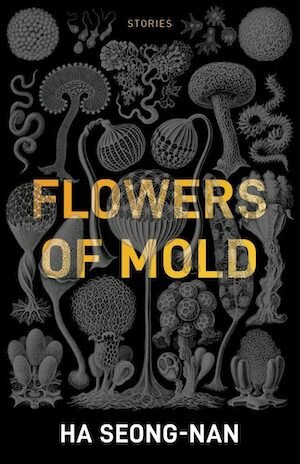

[Open Letter; 212 pp. Translated from the Korean by Janet Hong]

It must have been quite a while since I read a story collection, to be honest; I don’t tend to attach myself to them conceptually as much as longer constructions, for whatever reason: perhaps the continuous disconnection of starting and stopping that less intuitively-joined sets of stories require, rather than enabling reading in short bursts, as seems to be the major trend now, dissuades me from coming back, without the nails in the flesh that longer works allow; the trail of crumbs, the glue between. With a title like Flowers of Mold, though, and with the evocative descriptions of Ha’s “disturbing just below the surface” approach, I let myself in, and was pleasantly moved by the mechanics of what the construction of these stories, which do intertwine in oblique ways, allow to synthesize and build.

The most surprising thing, for me, about Ha’s method is her ability to create a logical, clear-uttered world that nonetheless continues to undo and reform itself simply by the bizarre range of sentences and details she weaves in. Surprising twists in sentence-ry are no new thing, for sure, and in fact can get old in being predictable in their surprising-ness, which all too fast becomes not-surprising because we are already used to being supposedly surprised, thanks to the late 90s wave of American short story makers who inadvertently co-signed the quirky voice that would, and often still does, characterize a certain kind of McSweeney’s-adjacent voice. So much of it eventually being mirrors reflecting mirrors reflecting something by now commodified to be “the way that we get weird,” which of course isn’t weird at all unless you haven’t read it: the state of many.

Ha’s weirdness, though, sentence-to-sentence, is all its own. For once, the weird-for-weird’s sake (which I do dig when done right) isn’t the mechanism, but seems to be instead just the way her stories must be told. The sentences are clear, describing action that sometimes connects to larger movements within the story, or the set of stories, but also may just be the way the information comes together, seeming chaotic when in fact it is of-order; the same way that Lynch’s films have a logic all their own. She seems, often, to be describing many different strands of action all at once, without always bothering to connect them directly, logically, above-board, but to instead leave gaps where the reader can jump right alongside her, creating vast momentum in small space.

There are so many examples of this throughout the book—the stories are in fact made of that kind of DNA—streaks and stops; close attention to a detail that seems wayward until it recurs. Look no farther, for instance, than the opening paragraph of the first story here: “Your watch stopped at 3:14. The second hand fell off when the glass cover shattered. Within minutes you were unconscious. During what seemed like a nap that went on a little longer than usual, the seasons changed in the front lawn, right below your hospital window.”

That’s not just a disorienting opening, meant to catalyze you in a moment that then falls into rhythm underneath, becomes a confusion that is over time placed into order, or even necessarily given plot points from which on a second read you will be allowed to more directly understand. Instead, Ha maintains that disjunctive associative motion into the next paragraph, too, creating a form of space that often prose has felt unable to summon in how there must be something to keep us close; the mystery must develop; the walls must direct us back to where we already have been. That’s not to say, either, that these stories are evasive in giving you a thread to follow, to keep you near enough that you don’t end up wandering away. Somehow Ha is able to high-wire that logical-surrealism into sections, flows of action, that even when they never cohere still gain magnetism by how the world we’re in keeps getting larger, more insane; that eventually there is so much mystery inherent in even something as simple as the apartment next to yours that you could never overcome its pregnant power.

So much fun, then, in finding all the ways these stories interact without calling attention to the grinding behind their sparks. A single sentence might use an image that had been part of the plot draw in one story as an adjective describing how a character feels (for instance, toothpaste?!?). Trashbags, hidden rooms, splintered mirrors, a particular undeveloped woman, accidents, models, surveillance cameras, blind spots, hotlines, secret sides of people, sudden trends in fashion or behavior: they crop up and pop in ways that make you realize there are undercurrents between texts, secret textures that are doing work whether you enable them in your attention yet or not—to the point, then, that eventually you are allowed to settle back into the flow of the ideas and let the signal flares bump into you like subliminal messages, rather than trying to stay alongside any one aspect of the narrative’s subflow; like you are in the midst of an experience, rather than being assimilated into witness.

Let’s just look at a single common paragraph from maybe my favorite story I’ve read in forever here, titled, “Your Rearview Mirror,” so as to reveal the amount of technical weight and neural realigning that a single section of Ha’s work is able to do: “He has spent the last two years on this cheap, plywood pedestal. During that time, it has snapped four times under his weight. From it, he has a clear view of the entire 3,600-square-foot Cosmos Shopping Center. It sells mostly clothing, but there are other businesses tucked inside the department store, such as a music store and a gift shop. In the middle of the man’s field of vision is the main apparel section. Garments that resemble the robes of an emperor hang from shiny, stainless-steel racks. What appears neat and straight at ground level looks crooked from above.” So many different POVs and means of analysis combined side by side here, as if they fit neatly, and they do, but in a way that feels multi-ridged, with pockets all throughout where one could dig, and find logic of the universe buried within them; aspects that make the world the narrative takes place in like an organism, not just flat. The curvature of the universe, perhaps, is the main character in all these stories; riddle with portals made to look like decoys for commerce, emotion, means of tracking where we are.

Outside of sentence level shifting within paragraphs, too, the particular construction of the stories larger body unto themselves is another way Ha really reinvents means of storytelling. Even when the direction of the story seems to flatten out for a minute, attempt to gather poise, it moves past quickly, toward the next incoming jut. Scenes occur that we believe we are slowly being unveiled into a narrative action, if one that we already know will not lay all its cards on the table, but allow us to try to decipher them from within; then, just as we seem to reach a moment where oblique understanding begins to settle, the scene then shifts and turns away, mutates its energy.

The story “Flag,” for instance, opens with a strange description of the power going out in a small town, with details like “Housewives who opened the refrigerator to prepare breakfast found blood dripping from the frozen pork they’d left to thaw, the meat turned a dark red.” and follows forward to an unnamed narrator (who eventually calls himself Monkey Boy) climbing an electricity pole to assess the source and finding someone’s clothes strung up along the line, as if someone had stripped down as they climbed; the passage ends with him wondering what happened to “the man inside” the clothes. Then the next section begins, taking up the bulk of the story in a journal-style format of a car salesman who becomes obsessed with a model who comes into his showroom, leaving behind the opening for a disorienting series of descriptions of his obsession and the disconnected trouble it creates; then, again, following an act of violence, we return briefly to the narrative of the opening section, shoehorning us into his position of still unknowing, unable to let it go, and vaguely, conspiratorially etching deeper suspicion into how all of these tangents must connect.

Because they do connect; Ha has put them side by side for a reason, perhaps one she doesn’t even quite yet know. It’s difficult to sense the identity of the author at all here, thankfully, making her presence as the author feel mysterious all on its own. So many enigmas upon enigmas we can only float within its gel, seeking seeds and flights of information that bring us closer and further from the facts at the same time. In this way, Ha’s avoidance of forcing images, ideas, even plotlines into ground allows the ground to remain enchanted, primed by the presence of the reader as a cursor in the story each themselves.

The power manifested in these blurred-map-like texts, and how they overflow with what at first might seem absurd points of connection, feels fresh, electric; like a path one finds beaten down into a woods that opens up around you until you are unable to find your way back, quite, to where you started. Ha proves that thought in narrative not only doesn’t have to be linear, or synthesize into meaning, but can even create mass that is greater than the sum of its parts; that by installing enough intrigue and evocation into more formal modes of storytelling, and changing momentum by one’s gut, there is still space to be created that is adjacent to our real world, but maintains points of access that we may enter through out thoughts—that though we may come out knowing less than we knew when we began, we are also closer to something language can’t describe.