Moved reading log to Substack. Free subscription here: Dividual.

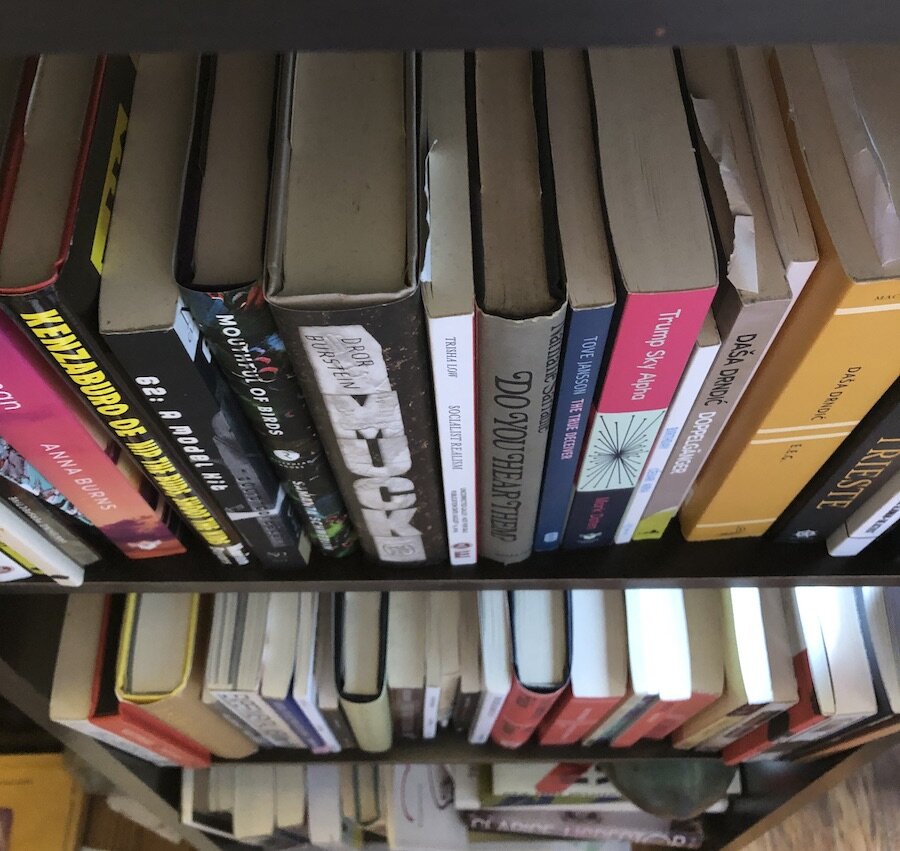

2019 Reading List

Easily the worst year of my life. It was a time, for the most part, when reading at all felt very hard to me; not only due to what had been being done to our attentions, to our spirits, but to coming to grips with my greatest fear, the death of my mother, from out of nowhere after several years before now seeing her lose her mind to Alzheimer’s, and being cut out from the degradation of it through an unexpected reckoning with cancer. I don’t want to get into all of that stuff here, but suffice it to say that there was a point some time last year, when I was less consumed with death and more with the daily aspects of living, and helping the person who created me to keep living, that reading was the last thing on mind. I quickly began anticipating that my mind would never be the same, that I’d always be too tired at the end of the day to get anywhere with reading. I read less in 2018 than I have in my whole life, a trend that seemed destined to continue into the next.

Somehow, though, maybe even in the deepest recesses of my grief, I found the feeling again; or the feeling found me. Where for a while I’d begun to accept that I needed relief in the form of stupid television, or even sports, the engine in me that thrived and bred off of the experience of sentences, paragraphs, suddenly reappeared; I could suddenly hear myself thinking again, somehow, between the lines of others, and from there out, like a disease, though one that heals rather than undoes. Anyway, I don’t want to get hypershit about my feelings, but I am thankful to have found and worked to rekindle the process of reading in the midst of what felt like living hell. There’s still a long way to go, probably forever, but I am so thankful for those who continue to make work in the face of where we are, including many people who I am lucky to call friends; I can’t remember how or when it would have mattered any other way.

Nocilla Dream by Agustin Fernandez Mallo

This trilogy really set the tone-bar for the year of reading for me; totally new in its approach and how it allows possibility to manifest and remain volatile in expression, rather than instantly commodifying ideas into fiction or even overarching synthesis. Have been recommending this widely ever since, as it feels like the germ of a new approach to writing w/o the plague effect that Reality Hunger and its ilk always seemed to project, from my view. Would be on my list of works to be introduced in schools worldwide.

The Complete Cosmicomics by Italo Calvino (reread)

History of Violence by Edouard Louis

Milkman by Anna Burns

Wonderful and creepy in all sorts of ways; usually I don’t read stuff after it appears on an awards list, and yet the reaction this novel got after it won the Booker was hilarious to me: how the Times review described it as unnecessary and led nowhere. You’d think during a period of time where we’re all feeling hazed and fucked more than ever, people would be looking for work that resets the bar, that forces us to look at that which we do not wish to (in this case, the Troubles in Ireland, though its paranoid and discursive voice feels as trauma-bent in the now as any); instead we’ve seen the trend turn toward even more I-central manners of speaking, as if the whole world is just in duck and cover mode, talking to itself. Milkman reminds me a lot of the energy of Bob from Twin Peaks but presented here in a nearly classical mode that fears no means of description, no matter how unwieldy; thank fucking god.

Nocturne by Tara Booth

Yours by Sarah Ferrick

Vanishing Perspective by Alexis Beauclair

A Tunnel To Another Place by Apolo Cacho

The Brick House by Micheline Aharonian Marcom

Nip The Buds, Shoot the Kids by Kenzaburo Oe

Oe’s take on Lord of the Flies, in a way, which assumed a very simple mode of rhetoric, and yet one that made me wish I were able to write something so simple and so effective.

Nocilla Experience by Agustin Fernandez Mallo

Though the first part of the trilogy above ended up being my favorite, I really like how much Mallo shifted his approach in the other parts of the series. He seems committed to the thing, rather than to what the thing is meant to be, or how it should be applied.

Nocilla Lab by Agustin Fernandez Mallo

62: A Model Kit by Julio Cortazar

Mouthful of Birds by Samanta Schweblin

SS harnesses a volatility of image and affect that we rarely get to see anymore in major label fiction; at times her work reminds me of Cortazar, in how moments can be held down and examined up against the other moments that surround them, becoming elastic for a while, rather than simply attempting to convey their information or entertainment. It’s the sort of effect that feels disallowed from most American fiction lately, a trend that I will likely never figure out. I keep telling myself I’m getting old, that the forms of expression people seek no longer align with even what seemed possible ten years ago. It’s not hilarious. Anyway, thankful for the Schweblin injection.

Muck by Dror Burstein

Hated every second of this novel, honestly, despite the author’s obvious intellect, said obviousness causing, apparently, the need for him to prove it on each and every page of this book that in the end felt as if it had no heart. You can be as studied and allusional as you like and it still won’t make the pages come alive if all you’re doing is trying to direct the language through the sieve. Muck’s a good title for it.

Socialist Realism by Trisha Low

Trisha is such a pleasurable thinker. My blurb for SR: “In years like ours, what a relief it is to be allowed into the mind of Trisha Low. With infectious aplomb and zero pandering to the mind games of social grace, Socialist Realism weaves together intimate and moment-defining considerations of heritage, religion, masochism, sexuality, authenticity, utopia, transgressive art, and so much more, laying bare the myriad layers and projections of a persona surrounded by duress and still in search of something more. Equally candid and and courageous, this meditation from the dark side of the heart may have arrived in the nick of time.”

We Are Made Of Diamond Stuff by Isabel Waidner

Do You Hear Them? by Nathalie Sarraute

The True Deceiver by Tove Jansson

My Documents by Alejandro Zambra

Cyclonopedia: complicity with anonymous materials by Reza Negarestani

The Book of X by Sarah Rose Etter

So happy for Sarah, having read this novel in several different forms over the time she was working on it, and seen it come into such strong form. Here’s the blurb I wrote her: "Taut, macabre, with wounds electric, The Book of X will take your head off while staring dead-on into your eyes. Move over, Angela Carter, there's a new boss in the Meat quarry, and she is fearless, relentless, ready to feast."

King of Joy by Richard Chiem

Juliet the Maniac by Juliet Escoria

Trump Sky Alpha by Mark Doten

Blackly hilarious and effective rendition of esp. the earlier Trump years, when every day felt like being blitzed and held down, whereas now it’s beginning to feel like something much more inescapable than we ever even realized. MD’s Dennis Cooper influence demonstrates the viability of creating wormholes and plot falls that keep the sentence-level pyrotechnics flowing forward into something larger than the book itself, which seems more vital in the Reality Hunger sense than trying to stay pertinent; that is, there is an energy harnessed here that does not balk under the weight of its ideas; instead, it flows forward under the pressure, becoming preternatural.

Birthday by Cesar Aira

Doppelganger by Dasa Drndic

Drndic is probably my favorite discovery of the year; her fearlessness, coupled with an incredible sense of tone and the line as it relates to image, put her work up on the highest levels of what literature can do. I haven’t yet fully figured out how to talk about her work yet, as it contains so many different kinds of mode, but suffice it to say that she’s a fucking BALLER. Everyone should be reading her right now, especially:

E.E.G. by Dasa Drndic

A masterpiece; just blistering and revelatory in its handling of history and authority, how terror infiltrates and blends back in to daily life, how it continues to change us even in returning toward silence. A book I will never forget.

The Activist by Renee Gladman

Rag by Maryse Meijer

The Blood Barn by Carrie Lorig

Really love the effect of Lorig’s ability to delve into the unknown (and the all-too-well known) of one’s self, unpacking nervous energy into sheets of language that seem able to exist no other way. The kind of book that I love just staring at, turning the pages through, feeling its acidity getting on my clothes, my face, etc. A kind of monolith-like approach to exploring trauma in a way that refuses to commodify it, but to wield it, almost like a spellbook.

The Taiga Syndrome by Cristina Rivera Garza

Animalia by Jean-Baptiste Del Amo

A rare case where comparing the work to that of C. McCarthy actually holds water; such a brutal creation, finding ingenious new ways to describe the violence that is done against animals on a daily basis, by corporations sprung from seeds our relatives sewed before the advent of viral information. Sweltering sentences, desperate syntheses of the various machinations hidden in our lives, and an emotional curvature within that enabled greatly by the author’s ability to command language onto that which otherwise just remains blood, meat, wind. Fitzcarraldo Editions has just been killing it; so thankful for them as a press that can be counted on for greatness, title after title.

Apparitions of the Living by John Trefry

Reup that press praise for Trefry’s Inside the Castle, which feels like a dream press for me, exploring the margins of work that remains evasive of definition. Trefry’s own work is likewise fantastic, here carrying on the Robbe-Grillet tradition with a mind-slurring evocation of sexual paranoia and obsession, including passages so rich with style that it’s no wonder Trefry is an architect IRL; his paragraphs are buildings, his texts refreshingly, compulsively encrypted against narrative as potential space.

I <3 Oklahoma! by Roy Scranton

My blurb: “With whip-smart, multivalent prose akin to Barry Hannah spliced with William Burroughs, I <3 Oklahoma reads like a hypermodern Heart of Darkness, aimed straight into the malefic gnarl of Trump's MAGA. The result is an epochal, brainbending prism of a road novel, catalyzing any branded icon that might crop up into its wake—from Deleuze to Taylor Swift, Beuys to Bonnie and Clyde, ISIS to TMZ—into an immaculate reflection of a nation mesmerized by its own free fall through oblivion.”

Trieste by Dara Drndic

Another vital work from Drndic, probably second to EEG in personal ranks.

Northwood by Maryse Meijer

Debt: The First 5,000 Years by David Graeber

Actually still working on the second half of this, as the scope and bandwidth of its data is a lifetime achievement, and one that recalibrated the way I’ve thought about money and its interaction all my life.

A Sand Book by Ariana Reines

Ash Before Oak by Jeremy Cooper

Vivian by Christina Hesselholdt

The Country by Ken Baumann

Experimental Men by M Kitchell

The Laws of the Skies by Gregoire Courtois

Vineland by Thomas Pynchon (reread)

Might have replaced Gravity’s Rainbow as my favorite Pynchon, at least until I reread GR hopefully next year. Hilarious and well ahead of the curve that led to where we are . Will there ever be another figure like Pynchon in America? Seems impossible.

The Crying of Lot 49 by Thomas Pynchon (reread)

Mason & Dixon by Thomas Pynchon (partial reread)

Malina by Ingeborg Bachmann

Another highlight of the year, though a heavy and complex one. One of the most emotionally charged pieces of writing I can remember in some way, in a a subterranean, nightmarish sort of way. The systems of language and affect Bachmann used to describe the female experience by citizens in Nazi Germany feels like a stranglehold of sorts, using such intricate means of POV and interaction between phases in the book that it feels like being smothered slowly and in due course. Effects of the prose unlike any other, really, and made of paragraphs that you could read over and again and still feel stung by. Need more of her work available in English translation ASAP.

The Milk Bowl of Feathers: Essential Surrealist Writing edited by Mary Ann Caws

People I’ve Met from The Internet by Stephen Van Dyck

Enjoyed the scope of this catalog of everyone the author had ever met online, going back to the earliest days of AOL chat rooms and the consolidation of the internet, but also felt disappointed that it never attempted to transcend the personal to larger means of thinking about its subject, or even a more robust texture resulting from the amassment of private data. Ideas are such strange things in this world now; reduced to headlines, never attempted to be nailed down, or given germ-body; just existing. Seems like that’s the more popular way to do it these days, so I won’t out myself as old as fuck, and even older at heart, it seems.

Feeld by Jos Charles

Moment of Freedom by Jens Bjorneboe

Sweatpants Paradise by Kyle Flak

Blood Meridian by Cormac McCarthy (reread)

A top 10 all time novel for me still (or was that Suttree?), and no less incantatory an experience reading it for the fourth time.

Child of God by Cormac McCarthy (reread)

The Fallen by Carlos Manuel Alvarez

Hall of Waters by Berry Grass

Unamerica by Cody Goodfellow

The Divers’ Game by Jesse Ball

Vincent and Alice and Alice by Shane Jones

Giovanni’s Room by James Baldwin

Prowler’s Universe by Larissa Szporluk

Trip Out & Fall Back by Joanne Kyger

Amygdalatropolis by B.R. Yeager

Probably my most infatuated-with book of the year by an American. If you could breed the DNA of a dream book for me, it would be something like this, though I could have read 600 pages of it; so vile and hyperdimensional and necessary in its rendition of the backblood of the internet, the phantom wreckage it is built upon, and what it does to people. Also just hilariously grotesque and full of danger-vibe. Do it.

As Consciousness Is Harnessed to Flesh: Journals & Notebooks 1964-1980 by Susan Sontag

The End of the West by Michael Dickman

Barf.

Who Wrote the Bible? by Richard Friedman

Had always been interested in learning more about the origin of the bible and how it was formed and edited and by whom. This book felt like a mystery novel in that way, laying bare some of the most basic strands of the biggest true conspiracy of all time. Interested in reading more like this.

I Remain in Darkness by Annie Ernaux

The author’s unedited journal from the period of her mother’s descent into Alzheimer’s, and the personal aftermath of trying to cope through it. This book provided some extremely crucial insight to the experience of losing my own mother to the same disease, and some relief in attempting to manage to want to continue living after seeing what society and life does to our most beloved. I have a lot more to say about this, obviously, but well, later, maybe.

A Slow Boiling Beach by Rauan Klassnik

Houses of Ravicka by Renee Gladman

The Punishments of Hell by Robert Desnos

“Waiting for Godot”/”Endgame” by Samuel Beckett (reread)

Dolly City by Orly Castel-Bloom

Reminded me a lot of an old fav of mine, Nikanor Teratologen’s Assisted Living. Comically nasty and interpersonally degraded to the point that we’re able to look more directly at the darkness that surrounds us, for once, not pretending it is only something to offended by, or even improved by, but to be survived. Probably a great book about parenthood too haha but what do I know about that.

Medea by Catherine Theis

The Memory Police by Yoko Ogawa

A fantastic concept for a book in the vein of Brave New World, but also so full of plot holes in a plot-driven novel that I found it irritating overall. Why do we have to bend these sorts of stories toward resolution and toward attempting to make a statement about something almost no statement will prove true through? I’ve never understood the impulse to try to calcify intentions to that degree, though again how else do you end up on a bookshelf at an airport? You can’t Instagram the void, but you can sure try.

The Faculty of Dreams by Sara Stridsberg

Johannes Goransson had been talking about this book in its Swedish form for years, so I was excited to get to experience it for myself. A fantastic and multivalent retelling of Valerie Solanas, that both attempts to depict her in the scenes of her own life, and to connect to the spiritual history of what she has come to represent. SS does a fantastic job of continuously altering and returning through the mechanisms of her approach to evoke a portrait of a being that goes far beyond its facts, and to in the process meld the impression of how a linear-esque novel can be assembled.

The Crying Book by Heather Christle

Notebook of a Return to the Native Land by Aime Cesaire

A hellscream, with such depth of spirit in the midst of atrocity that it feels like a revolution of spiritual intent; should be required reading.

The Hermit by Lucy Ives

What a refreshing, post Wittgenstein-like assemblage of fragments and ideas, about reading and writing, experience and meaning; feels like a tool chest of sorts, full of ideas that inspire the creation of ideas. Need to read more of her work now.

Armand V by Dag Solstad

A quite bizarre construction for a novel, told in footnotes that drop you in the wake of the aftermath of the parts of narrative that do not appear. I like the book best when it gave up circling the strands of its own narrative and burst out into speech bordering on the quasi-philosophical, much like the Ives book above; sometimes the work of following the fragments and their recursion into plot felt a bit too far of a reach, though also conceptually strong enough to want to continue being brought forward in it. Solstad seems like a writer’s writer, like Ives does, in that way where you are invited into the play of the work of creation, or at least into the illusion of doing so.

The Last Thing I’ll Ever Write by Adam Lauver

Garden, Ashes by Danilo Kis

The first section of this novel made me cry while reading it while very stoned, thinking about my mother, and how the conception of her in my own mind has changed, and continues changing, over time. The rest of the book blurred coming out of that, and I don’t want to remember it another way.

Screen Tests by Kate Zambreno

Nice to spend time in KZ’s brain, following her through her obsession and their indexing throughout life. This work felt honest and open to exposure in a way few books being written today do, in laying bare the thoughts behind her thoughts.

Old Food by Ed Atkins

The Beekeeper: Rescuing the Stolen Women of Iraq by Dunya Mikhail

Our Death by Sean Bonney

RIP

The Years by Annie Ernaux

Reminded me of Ourednik’s Europeana for how it condenses into massive paragraphs whole cycles of cultural history, coupled w/ Ernaux’s development as a person maturing alongside the larger mechanism of societal expansion and adaptation, how times are and how times change, shuffling back and forth throughout a meticulously deep archive of the experience of living. Moving, magnetic, and overflowing with the otherwise soon to be irretrievable data that fills up the backlog of one’s life.

Belladonna by Dasa Drndic

Avoka by Elle Nash

Walking by Thomas Bernhard

The Crisis of Infinite Worlds by Dana Ward

I Hotel by Karen Tei Yamashita

The Crisis of Infinite Worlds, Dana Ward (2014)

[Futurepoem, 145 pp.]

Had been pulled to this book for a while by its title and the sensation of its cover (srsly), though not to the point of buying it until finding it tucked on a shelf at a store, having long forgotten of its existence. Nice at times to let a book maintain a distance for a while and continue to contain the possible potential of what it could be without exposing it to what it actually is.

I think then I really wanted to be absorbed by this when I finally opened it, and I knew already that it would likely not fit into any of the possible conceits I could assign it—knowing well as a regular purchaser of Futurepoem titles how oblique and quasi-intentionally anti-tag they end up being. Like Fence, they seem to a publisher who allows a book to exist without needing its explanation and direction to have space; a wonderful thing, if also one that creates a serial apparition of pretentiousness or ‘why’ to people suspect to not being allowed to follow along, who don’t like to read in a way that feels like being washed over, over and again. But I love that feeling, and as I read the first few pieces I thought I might come to appreciate this book the way I think I wanted to love Donald Dunbar’s Eyelid Lick before I read it, years ago, and then decided that I found the book (DD’s) irritating in its provocative evasiveness, its playing coy with equal doses of references and abstractions beyond the point of meaning, beyond even ridiculousness, which eventually instead began, in that case, to feel like a state of being, or a drug, more even than a tome or text; I mean that like that I accepted I would never fully understand the book, nor was it meant to, thus opening it to the possibility of returning to its possibilities forever, or at least as much as anyone might like—bearing its own mythos rather than an inherited one, perhaps, though also throttled by its authors’ fascinations, experiences, etc. This is, for me, one of the great powers a book can manage to achieve—like a window made of other windows.

I ended up long-term loving Eyelid Lick in this way, for its capability, and think of it still as a book that succeeded in assembling a new form of simulating existence while appearing to intend to disappear into itself rather than persist. I did not, however, end up loving The Crisis of Infinite Worlds in that way, at least so far, despite the similarity of initial intrigue mixed with consternation against what would actually appear. The book is made up of a variety of forms, including more formal poems (of course dedicated to other poets), and many concept-constrained essays, often self-referential and culturally tagged in equal parts, switching between a banal, matter-of-fact writing style, and intentionally theory-heavy recursive logic, sometimes to the point of “colorless green ideas sleep furiously” level thrust, often all within the same paragraph. The effect likewise continued shifting, from so flat in affect it’s like why are you telling me this, to elusive enough to make you double back and read a line again, to intentionally ridiculous, the latter of which began to accrue at a higher and higher rate as the rate of willingness on my end ran dry. In fact, by the end I found myself marking with little slips of paper the pages that irritated me more than other pages already had, and not directly marking them with a pen in fear that I’d one day look back and think I marked them because I appreciated what they said.

Whereas EL seemed to be the kind of creation that applies itself to the mind in such a way that it feels spiteful at first, then more slippery, eventually engendering your imagination with greater depth in how it resists rather than how it corresponds, TCoIW never managed to transcend, for me, the vogue of that irritation; the prickliness of the hyper-awareness with which Ward attempts to solidify observations, transmutative nuances of thinking and observation, ‘surprising’ personal references (such as in the closing essay which takes its title and its subject from Alvin and the Chipmunks 2: The Squeakquel). It all began to feel, I don’t know, still trying to force itself to go somewhere, despite begrudging the possibility of ever doing so all along the way? Like watching a video of one’s self performing a temper tantrum, full of tongues, at an age a bit too old, commenting on it with meta-lenses intending to seem to want to make low of high and high of low over and over, creating a system wherein no attention is to light long enough in fear of actually saying something?

On one hand, this effect is a delight: Ward is obviously brilliant with an ability to generate fluid structures of analysis to almost anything he wants. Reading his ‘time is of the essence’ style construction, through thoughts about reading, about objects, about being, about writing, memory, art, ideas, his best lines seem to enjoy their resistance to causing pleasure, or to wearing its friction like a toupee, and yet eventually the explorative intent seems to run up moored before the gloss has time to dry, leaving the thoughts sticky, maybe, or tacky, or intentionally dense. Seeing how the text manages to steer through so many essences of perspective—if all clearly the same thinker—becomes part of the fun of it: I found myself continuously wanting to keep reading to see where it might go, how else it might continue to defrag itself as it compiles; and I do enjoy, in a way, reading things that make me eye-roll, because I feel they’re fucking with me, or they are fucking with themselves—or U like to feel tension between the perception of the author’s most sincere points and how we’re supposed to manage being handed so much information that goes nowhere back deeper back into itself.

The way this book crops up among the 2010s framework of ‘experimental poetry’ seems indicative of something I feel aligned with in general, as a person who wants the system mangled, but at the same time feels clique-bait-ish in presentation, and even also in intent. I read the blurb on the back of this book telling me how this text contains magic, sleight of hand, but all I end up coming away with is the miraculous vapid again, if clearly bisected with the way Ward feels witty, if not wise, and funny, if not funny. Such a contraption of intentional meta-existential contradiction-speak is obviously honest, and surrounds us in the way all information now seems to have taught itself to, and in many ways the absence of an empirical relation or even firm direction but through broken aspects of nostalgia is more true of a subject than most subjects, if we have to say, even more so for how impossible it is to ever clench.

This book does succeed in that way, creating an object that refuses to even want to be an object of reflection, much less meaning. And yet the book is full of attempts to begin from somewhere: for instance, there’s a long, detailed and more plainly spoken essay about the birth of his first child, and the early days of feeling in fatherhood, which honestly felt tedious against what felt like the much more beguiling sections, such as the more overtly lyric-oriented poems, which do often contain dazzle. Another piece, titled ‘Things the Baby Likes (A-Z)’ seemed hilarious and strange in how it forced one to imagine a baby liking “Fraggle graveyards, Food comas, Formalism,” though then there are 20-some pages where Ward then writes a mini-essay after each, each acting like a little meta-memoir, which in total feels more like what the book wants to be: a synthesis of realism and conceptualism, in which nothing ever gels between.

What I’m trying not to say about this book is that it feels like a book that has nothing to say and yet is extremely qualified to say it, and from a voice that at least knows how to galvanize its fear. It feels ripe for the plucking by the same sort of critic who turns quickly to assess something as ‘navel gazing,’ as if the world isn’t made of navels. But still, I can’t help but wanting to be standoffish from this platform: to wonder: why? Why does Anselm Berrigan blurb the book saying, “This work is saving my stupid ass.” as the main header line in the book’s blurb, as if attaching a quip like that from a person like that should or could automatically legitimize its reason for existing? Nothing should exist, of course, but if it’s going to, on what terms? Or, to what end? Coffee table jackoff spritzer juicing? Happy fuckoff handstamp PhD noise? I don’t know. I don’t know that anybody knows; least of all the cadre of poetry-world insider-outsider folks whose participation in the formation of a publishing universe where no one has power, and yet it is conducted through the attachment of these names, of style over substance to the Nth degree, even in the agreement that nothing matters.

I’d say something is revealed late in the book when the author discusses the generation and means of publication of the book itself: that he wrote it as an assignment, knowing it would be a book, written after having received agreement to do so from a friend who ran the press. His description of the desperation and near-sickness creating by seeking time to think and write, particularly as a new father, felt true to me, sure, and gave the work retroactively the feeling of a time-document, a piece of space-shard, rather than something architectural, or even drug-like, the way Dunbar’s book felt. I’d also say his forthcomingness about the issues surrounding the creation do bear interest, in the way a car crash does, or a snuff film. But also, jesus christ, who fucking cares? Do I have listening to poets talk about the politics of becoming and being poets, as if all it takes is more than saying so and showing up? The emphasis on who and where and when, and how miraculous, versus the more private sensation of facing up to one’s self in the work, much less to the darkness, feels defeated, line by line, even while beautiful as language, as obfuscation, as a fakebook of jokes infused with artificial meaning in a world where meaning cannot be anything but. The mutant status the book gathers as a result of so many different kinds of thinking feels much more essential to it than any of its individual components, in the end, which is in vogue by now, for sure: these days eking out anything even moderately defiant to form, and often hyper-proudly, feels like the stripe that most anyone could imagine that they need: that the work is done because it’s done both assiduously and without bounds but in the mind, and at least it’s not another set of verse chord verse tropes by whatever hell poet people don’t want to be like anymore.

So I guess, in the spectrum of it all, while I didn’t love the experience of reading this contraption, I’ll take it one over a bunch of other things I’d have to take if ulterior conditions didn’t exist; and I do enjoy being irritated in a fresh way, and irritation is godly; but I still can’t say I think it gets there. And I can’t say I can imagine how it could save someone, unless that person was about to be shot unless they could wax weird about how much Evian fills a canyon, as Ward refers to, or what Mariah Carey’s “Fantasy” sounds like on a piano with the “ebullience ripped out.” I can’t remember where I read the term recently “meta-diarist” but you can place this catalog of crisis-as-absence in that continuum for certain—and at least there are enough friends of friends of people who can theorize and type to be able to gather enough sparkle to imagined they’ve experienced something bananas, even gorgeous, the way nails are gorgeous, both on fingers and in pails. It’s definitely the kind of book that refuses to be diminished quickly as a reader’s memory, for what it embodies more than any particular line or section, even taste. I suppose I’ll keep this thing around. Maybe I’ll pick it up sometime and look again and see what happens.

Walking, Thomas Bernhard (1971)

[University of Chicago Press, 104 pp.]

An earlier work by Bernhard, and one of the few of his I hadn’t read. Laid out three unbreaking paragraphs, the novella primarily assumes a form Bernhard later used elsewhere—as Brian Evenson points out in his brief introduction, re: Correction, which I think was the first of his I read, and remains a favorite (though Extinction still tops that list)—where most of the body of the work is presented as thought delivered in speech by a character in relation to the narrator, creating a focused absence in which the ideas are allowed to resound. Thus Bernhard is able to have insane shit spoken, such as: “Anyone who makes a child, says Oehler, deserves to be punished with the most extreme possible punishment and not to be subsidized.” This logic becomes supported by B’s patented would-be ever-quasi-suicidal roving outlook wherein life is misery and no one actually wants to live their life, because nothing can be known or even spoken, where intellect is misused and passed over both by the state and by the people, and all are forgotten soon in death, etc. Mostly elementary viewpoints for anyone reading marginal Bernhard work, but still worth a chuckle and a nod along the way.

The middle and closing thirds don’t do much to extend these observations, other than providing fragmentary details about how a mutual friend of the two main characters eventually went insane trying to find something to hold onto in his thoughts, which is taken by Oehler as the obvious way all thought will turn out if pushed deep enough into. Meta-sentences calmly project a nearly farcical scene where the friend loses his shit in a pants store as he tries to insist that the pants are made out of bad fabric, to the point of being see-through, despite the pants’ maker’s insistence they are fine, erupting in a row that leads the thinker to snap and end up being committed. There is some talk over the uselessness of visiting that friend in the asylum where he now resides, suggesting that once a person has gone insane it is useless to try to visit them or find hope, again said by Oehler, which rang less true to me than his other dark positing; as even though perhaps the insane person is no longer able to identify or speak directly to a visitor, they do possess a more rare connection to the possibility of anti-logic revealing more truth than logic as it corresponds to reality.

I could not help but think of visiting my father in the rest home during his respite stay when my mom needed a break from keeping him at home, and how free he seemed unto himself spiritually there, released from the possibility of knowing or depending on anything, and relegating to speaking to carpet, to air, to others equally divulged of their ability to try to parse. Can’t hold that against young Bernhard, but something to be said of the idea of exploring a lifetime abandoned by its own reality, and thereby, if one is willing, being forced to face what madness might eventually come for you as well. How time changes in that conditioning; how one can unlock partitions in the self that have accrued there without their knowing, like a cyst full of data that only bursts when all other possibility of “competent” outward expression has been removed.

“For it is clear that, in this state, only what is stupid, impoverished, and dilettante is protected and constantly promoted and that, in this state, funds are only invested in what is incompetent and superfluous.” That would have really gotten me going in my early 20s, though now it seems like expecting to see Black Dice on the Top 40. It gets old, but then again I still find myself keyed up coming out of recent movies like the heavily lauded Parasite wondering what in the world happened to people wanting more from what they consume than memeable jokes and flat allusions to class revolution, when really the existence of such a film is a product of the contraption having caught up with the catchwords that make those who teeter on the edges of wayward enough to bring them back in just in time. It feels like the recent Domino’s ad where they are pleased to offer you “insurance” on your pizza order if they get it wrong, auto-correcting the possibility of their likelihood of getting it wrong and swearing they’ll take care of it as an asset they can use to sell you more pizza. Plain as day. Out in the open. Not even trying to hide in anything but the assets they know you’ll read and report the headline and won’t click. As if being exhausted could be a revelation. As if there could ever be an understanding of death among the living, no matter how many times you breathe it in. Be it to say: losing your shit over a pair of pants being made shitty won’t land you in the nuthouse any longer, because we’re all already in the nuthouse, and so long as your still capable of ending up in a store that sells pants, for whatever reason, you might as well be a fucking senator; there’s hardly a difference.

So is this a novella, by now, more about how we got here than where we’re headed? About how it was already too late before we even actually imagined we began on ground never so blank and built on holes? I guess, in that light, even young Bernhard is still Bernhard, the recursing meditative dickhead with ire to spare, and revisiting through echoes the earlier modes of thinking that helped bring one, in their best moments, from standing around with their head tucked under their wing, is the kind of work that needs to be on shelves, not yet a pill-form, and like the lip on a hole that you wouldn’t mind being back at the lip of rather than so far down beyond the bottom you no longer wonder when there’ll be a bottom.

Too, that the narrator never comes around and offers his opinion on Oehler’s speaking, that he simply absorbs it and moves alongside in seeming lockstep, feels about as accurate as hanging out with people has felt to me for some time; like wandering around as if at a disembodied window, buried beneath curtains, uncertain how or why to interject. It is nice how the work creates a space from which we can observe the ongoing without trying to press in, without being instructed or even presented information that we are forced to reckon with; that blank space feels like the most modern aspect of the work here, and the most likely to elongate if provoked, knowing nothing else, as we do, about who has been relating all this information, like any would-be person, including the apparition of a god who’s given up.